Atlases and their maps are the most truthful books. They offer as well endless untold stories and mysteries for a boy, and an old man. Rand McNally showed me wilderness, and I’ve never been the same.

It’s the summer of 1970, and my mom, brother, and two sisters are homeless. We’re staying in a cheap motel on East Colfax in Denver. It’s my 12th birthday.

A month earlier, my mom packed the five of us and five tattered suitcases, and after my dad went to work at Dupont that June 26, we left my hometown of Niagara Falls and that violent, alcoholic man forever.

She left him a one-line note: “We thought you’d be better off without us.”

I never saw him again. He died six years later of his addictions.

My single birthday present is a Rand McNally Road Atlas — the big format, still in use today, with one U.S. state per page, or sometimes two pages for the bigger states like California and Texas. My mom found the atlas somewhere, while she was out looking for jobs.

She will eventually find three jobs, and we’ll start a new life in the West.

The atlas is a little ragged, and it is one of the best birthday gifts I’ve ever received. Ever. I spend hours laying on the bed in that motel, looking at the towns, cities, highways, landmarks, lakes, shorelines, coasts, and all the big empty spaces in those big square western states.

Colorado, my new home, is the most intriguing of all those big squares.

From East Colfax, I can look to the west and see the Rocky Mountain peaks. They have snow in late July! One day I tell my older sister that I will walk over there, to those mountains, but I have no clue of their size and scale and therefore no idea of the distances from east Denver — 70 miles or more.

My sister laughs at me. 50 years later, she still reminds me of my naïveté at age 12.

At 12, exploring the intricate geographic artwork from Rand McNally is my first exposure to wilderness and places empty of men and their constructions. I’m discovering the idea that maps — and therefore our world, my world — have big, wide places with no roads or towns but are full, with mountains and national forests and lakes and deserts.

A year later, after the five of us settle into a tiny, frayed 2-bedroom duplex, I join the middle school camping and hiking club, and I walk into the Colorado wilderness for the first time.

I’ve been walking in wilderness ever since.

My mom died years ago. I don’t remember if I ever asked how she knew that maps and Rand McNally could bring me such joy. Was it purely a random act? Did she stumble upon that ragged atlas somewhere and grabbed it on a whim, because she had no money to buy birthday gifts?

Or did she know I loved maps, had seen me get lost in them somewhere, perhaps in the Encyclopedia Britannica at our old house in Niagara Falls, or in the in-flight magazine on that long flight from my father and my childhood to a new world?

With her likely accidental brilliance, the vast wild places of the west settled into my soul, starting with the mysteries of those big empty spaces in my Rand McNally atlas, and the unspoiled outdoors has inspired, informed, and animated my life continually.

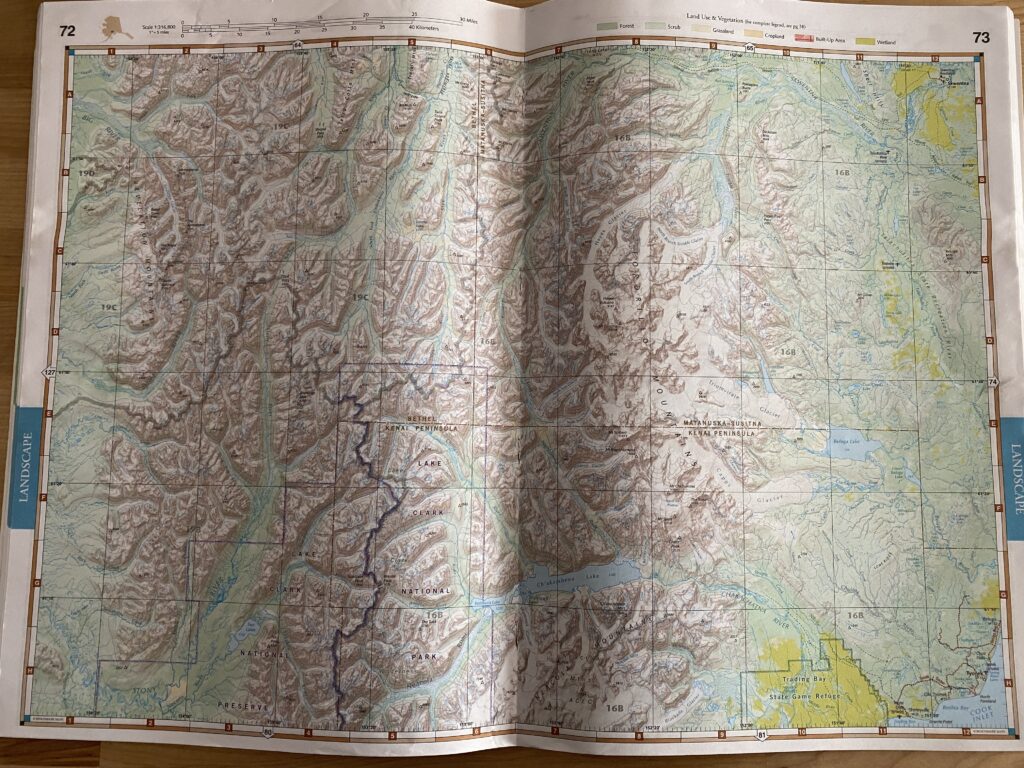

At age 64, with my wife, I visited Alaska this year (2022), for the first time. My shared history with her as well is grounded in wilderness, mountains, and the wide outdoors. Before we left, we purchased one of those big recreational gazetteers that have become so popular.

The format, size, number of pages, and general feel of that new Alaska gazeteer reminds me of that old Rand McNally road atlas from 1970. I find it comparably fascinating, fifty-two years later. The 64-year-old me finds this Alaska version of the map experience as enthralling as the Rand McNally version when I was 12.

The open spaces of Alaska dwarf those of the lower 48. Some tracts of untamed Alaska wilderness are larger than many states.

I discovered again that of all the books available in the human world, atlases and gazetteers are perhaps the most truthful and the most beautiful.

By contrast, other forms of ‘nonfiction’ are more subjective and interpretive. History is always selective and narrative, and always reflects the biases and inherent limitations of the historians and the central focus and the themes of the work itself.

Biography and memoir are variations of history. They are probably more biased and subjective, as individual works and as an entire genre.

Science textbooks and virtually any other non-fiction books also must reflect the perspective and attitudes of the authors and the ever-evolving status of the subject matter — including science. (Technical manuals may be one exception, but they are far more dull, arcane, and are often poorly and incompletely constructed.)

But the atlas is composed of highly accurate facts, as maps, data, coordinates, mileage, terrestrial precision, and proven details, and as I discovered in 1970, those facts can also suggest a far richer narrative as countless stories, history, and human decisions. Virtually every detail in a map or an entire atlas includes some aspect of human history and human endeavor and suggests endless questions about how that history unfolded.

To the 12-year-old discovering his new state of Colorado and his entire country for the first time, the stories and wonderment were boundless.

Why did they put that tunnel there? How long did it take them to build it?

Why does the railroad start or end in that little town?

What is found in that big empty space out west? Does anything grow there? Has anyone ever explored that? Does anyone live there, and if so, who? Why? How?

Why are the counties in the east tiny, and the counties in the west huge?

Why does that otherwise straight state line have that little indentation? What’s there?

Now, the 64-year-old mind explores that Alaska gazetteer.

The open spaces, compared to Colorado or Nevada or Utah, are staggering in their size — no roads, towns, cabins, or airstrips — only the place names that humans have attached to everything.

If I could magically add the entire history of human activity to this Alaska map — from footsteps, vehicles of any kind, any means that people have traversed this ground including horses or dogs – how much of the millions of square miles have been explored at some point in history? How much has never been seen or touched from the ground?

And regarding those cabins and remote airstrips – Alaska is unique in the use and frequency of those. Many are described as ‘private’ on the maps. How primitive are they? How do you get to some of those cabins when they’re surrounded by thousands of square miles of trackless wilderness? And why do some say private and others don’t?

One day, before my days are up and as long as my body will allow, I will return to the Alaska backcountry and experience a few more of those open spaces, those wild empty places portrayed in the maps.

Such has been my experience of our wild places and the documents that map them.

The key focus and theme of my writing, teaching, speaking, and research is ‘experience’ — how all outcomes in business and in life occur only through our experiences, and the importance of creating exceptional experiences for those we serve and finding superb experiences for ourselves to enrich our lives.

My love of maps and their representation of the territories of my life, especially the wild, open, free, and pristine, have been some of the most exquisite experiences I’ve ever known. Or ever will.